This article draws on the World Bank’s 2025 ProBlue Report: Accelerating Blue Finance: Instruments, Case Studies, and Pathways to Scale.

Marine ecosystems sustain more than three billion people and anchor industries ranging from fisheries to tourism, shipping, and coastal protection. They also play a vital role in regulating the climate and supporting resilience. Yet decades of overfishing, pollution, and warming seas have pushed these systems to the brink, generating mounting economic losses. Meeting the financing needs for marine restoration and resilience will require an estimated USD 1 trillion by 2030—a scale that public budgets and philanthropic funds alone cannot reach.

This gap has brought blue finance to the forefront of the sustainable-finance agenda. By structuring capital flows around measurable ocean outcomes, blue finance aims to channel private and blended capital toward the protection and regeneration of marine ecosystems. The World Bank’s 2025 PROBLUE stocktaking report offers one of the most comprehensive overviews to date of how governments and partners are deploying these instruments, what has worked, and where systemic barriers remain.

A Landscape of Evolving Instruments

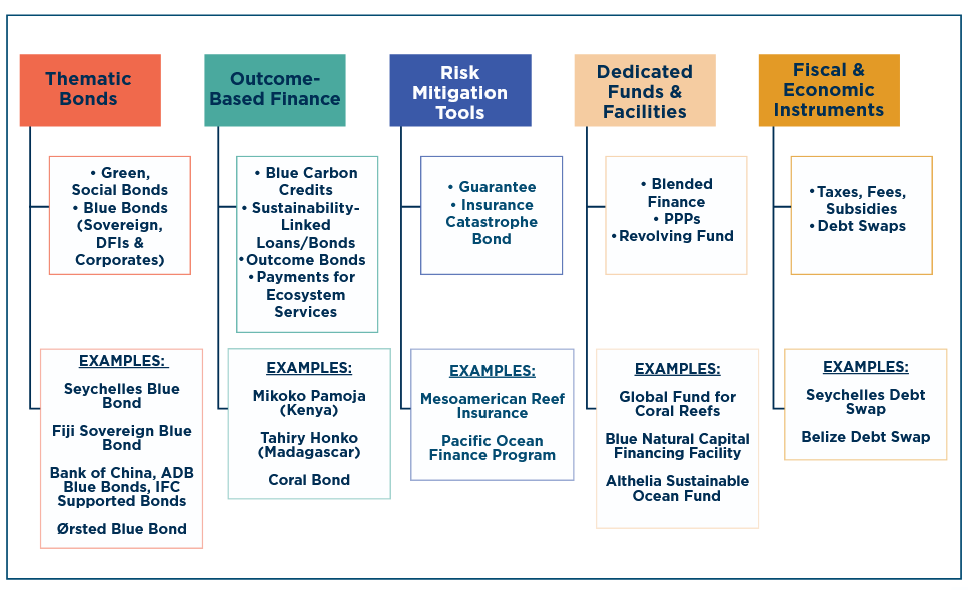

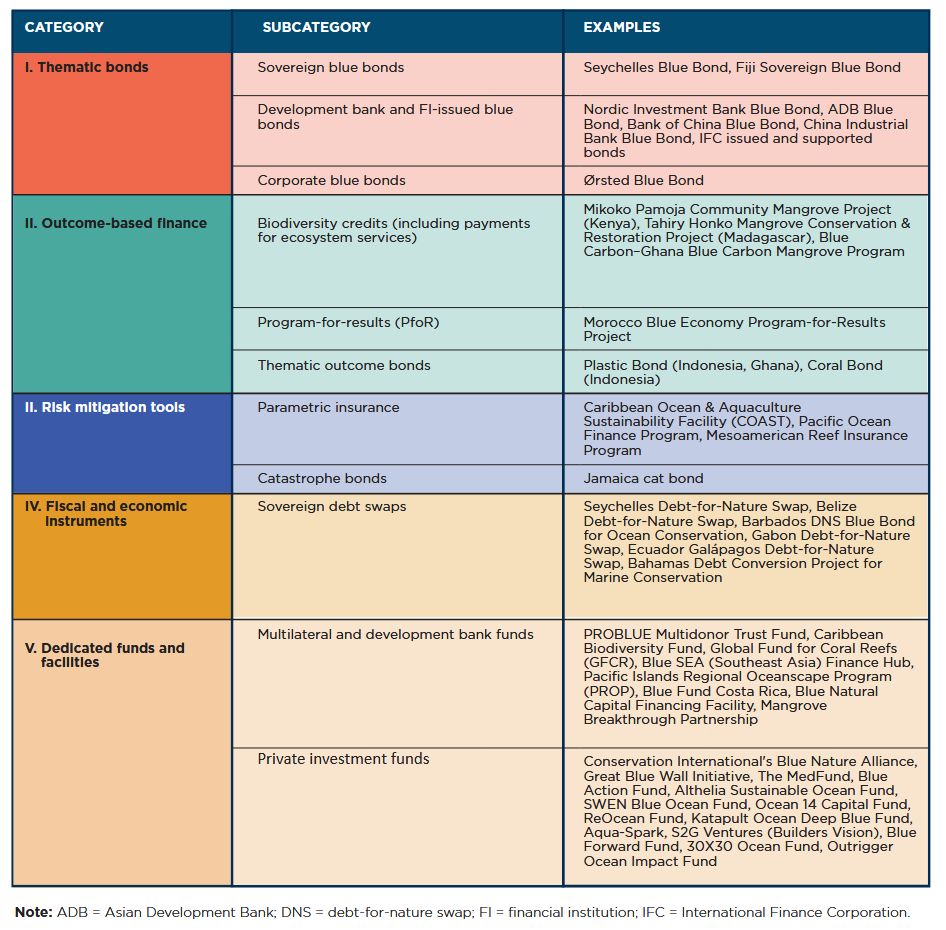

The report identifies five broad families of blue-finance solutions, each mobilizing capital through distinct pathways.

- Thematic bonds — such as sovereign or corporate blue bonds — use fixed-income markets to fund marine conservation and sustainable fisheries.

- Outcome-based mechanisms — including blue carbon credits and sustainability-linked loans — reward verified ecological results, aligning investor incentives with environmental impact.

- Risk-management instruments, from parametric insurance to resilience bonds, buffer coastal and marine sectors against natural-disaster losses.

- Fiscal and economic instruments — debt-for-nature swaps, taxes, or targeted subsidies — integrate conservation spending into national fiscal systems.

- Dedicated funds and facilities, often structured as public-private partnerships or revolving vehicles, create long-term financing channels for blue-economy investments.

Together, these tools form a modular “menu” rather than a single blueprint. Governments select combinations depending on their debt position, institutional capacity, and policy priorities.

The report delineates the case studies below to illustrate how countries and institutions are experimenting with diverse mechanisms to mobilize finance for marine sustainability — from sovereign bonds and community-led carbon projects to innovative insurance and debt-conversion models.

Implementation and Effectiveness

The experience of countries implementing blue finance instruments shows that success depends less on the tool itself than on how effectively it is adapted to local priorities and systems. Governments have used blue finance to achieve a range of policy goals, from managing sovereign debt and creating fiscal space to derisking investment and mobilizing private capital.

In debt-stressed economies, debt-for-nature swaps have reduced repayment burdens while directing fiscal savings to long-term marine protection, as in Belize’s coral reef conservation program. To counter persistent underinvestment in marine sectors, blue bonds—often supported by development partners—have mobilized capital for priorities such as sustainable fisheries and marine spatial planning, as demonstrated by the Seychelles issuance. Facing intensifying climate and disaster risks, particularly in small island states, governments have turned to parametric insurance to provide fast, rules-based payouts after extreme events, strengthening resilience and response capacity across the Caribbean. Meanwhile, outcome-based mechanisms such as blue carbon credits and sustainability-linked loans have channeled finance toward coastal restoration and mitigation projects in carbon-rich ecosystems.

The uptake and effectiveness of these instruments have varied across countries, reflecting differences in institutional readiness, technical capacity, and policy coherence. This underlines an important lesson: blue finance is not a fixed model but a flexible framework, a menu of options that must be strategically matched to the problem, the chosen financial mechanism, and the systems in place to deliver results.

Enabling Frameworks and Technical Credibility

Effective blue finance initiatives are grounded in supportive policy and regulatory environments that align public goals with capital flows. Mechanisms such as blue bonds, blended structures, and sovereign-linked instruments have succeeded when embedded within coherent national policies and fiscal systems. Drawing from the evolution of green finance, the introduction of taxonomies, sustainability principles, and performance-linked terms has reduced transaction costs and improved investor confidence. In smaller and credit-constrained markets, guarantees and insurance tools have created credible entry points for investors and multilateral partners to co-structure investable, results-oriented programs.

Equally important are the technical foundations that underpin credibility. Robust data systems, environmental baselines, and verifiable impact metrics have proven essential for transparency and long-term investor trust. Collaborations with scientific institutions have supported the development of standardized methodologies—whether for blue carbon accounting, plastic reduction tracking, or insurance triggers—enabling performance-based structuring and adaptive management. These efforts have not only de-risked capital but also reinforced the environmental integrity of emerging blue finance models.

Inclusion and Coordination

Social inclusion and stakeholder coordination remain pivotal to the success of blue finance. Locally grounded models, such as co-managed fisheries and community benefit-sharing schemes, have enhanced social legitimacy and delivered broader co-benefits, including job creation, gender inclusion, and improved governance. In regional contexts, coordination platforms have helped countries harmonize standards, aggregate financing, and jointly manage shared marine resources.

However, challenges persist. Gender equality and social inclusion are still under-addressed in many blue finance transactions, despite promising examples such as the COAST fisheries insurance program, which incorporated gender-responsive design elements. Expanding these practices will be key to building blue finance systems that are not only financially sustainable but also socially equitable and locally owned.

Closing Reflection

As the global community looks to scale ocean investment, these lessons point to a clear direction: blue finance must be context-driven, data-grounded, and inclusive. The diversity of instruments now available offers governments and partners a powerful toolbox—but impact will depend on the frameworks, institutions, and social systems that sustain them. If effectively integrated, blue finance can evolve from a collection of pilot projects into a coherent architecture for ocean resilience

Read the full report here:

References

Source: World Bank. (2025). Accelerating Blue Finance: Instruments, Case Studies, and Pathways to Scale. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. PROBLUE Program.